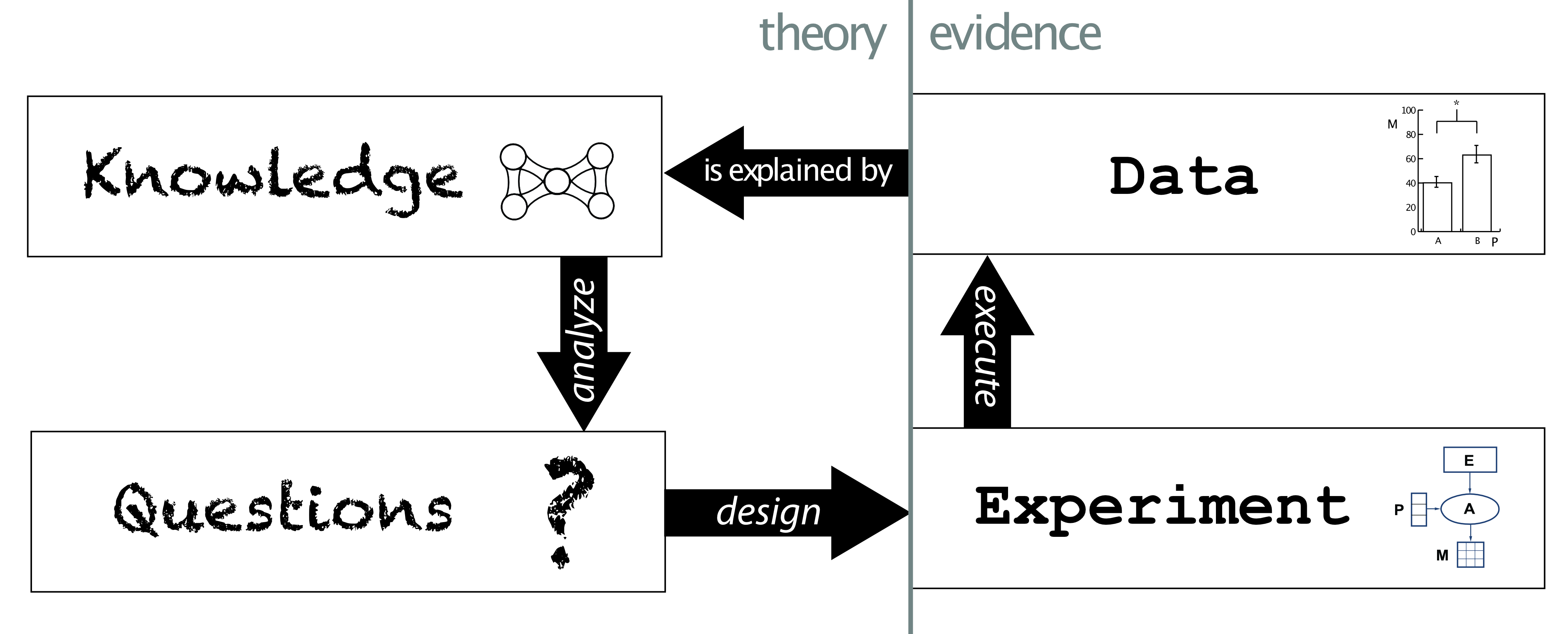

At its heart, scientific work is unlike any other because it must incorporate experimental evidence into its knowledge lifecycle. A simple way of viewing this is shown below:

This depicts the ‘KQED’ cycle:

- how knowledge may be analyzed to generate questions;

- how those questions may be addressed by designing experiments;

- how those experiments may be executed to provide evidence (or ‘data’);

- and how our knowledge must then be updated to provide adequate explanation for that data.

This construct is fundamental to the pursuit of Scientific Knowledge Engineeering (SKE), which seeks to develop computational approaches to represent, generate, and empower scientific knowledge in any of the forms that it naturally arises.

These forms could be:

- Scientific Publications (text, figures, etc).

- Data, either in online repositories, locally-defined data files, or collections such as laboratory notebooks, etc.

- Ontologies and other formalizations.

- Data processing software, such as Scientific Workflows.

This blog is inspired by participating in version 4 (part 1) of the ‘Practical Deep Learning for Coders’ course provided by FastAI and is intended to evolve my SKE-driven perspective (painstakingly acquired over the course of a 28-year career in academia) into a faster, more pragmatic approach that leverages the full power of modern machine learning as taught and advocated by the folks at FastAI and my amazing colleagues in the data science team at CZI.

This site is built with fastpages, An easy to use blogging platform with extra features for Jupyter Notebooks.